Silvia Foti über Jonas Noreika

Buchrezension von Donatas Januta

Veröffentlichung mit freundlicher Genehmigung von Lituanus.org (Lituanus ist eines der wichtigsten litauischen Exilpublikationen)

https://www.lituanus.org Zuerst erschienen in Lituanus #68 1-2022

Donatas Janutas Rezension ist gut...kommt aber zu dem genau gegenteiligen Schluß wie ich. Meine Anmerkungen zu seiner Rezension unter diesem Text!

A BOOK REVIEW BY DONATAS JANUTA

(LITUANUS VOL. 68:1 2022)

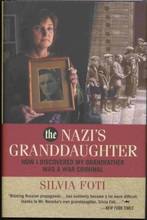

In an interview published in the Lithuanian publication 15min.lt on November 28, 2021, the author admits that her grandfather was not a Nazi, even though in the title of her book, The Nazi’s Granddaughter, and prominently on its cover, he is accused and presented as being a Nazi. Thus the book starts off with an admitted falsehood even before one gets to the first page of the text.

The author explains that this was a marketing tool to promote the sales of the book. Though she states that the Nazi label will be removed from the second edition of the book, she seems unapologetic for having falsely defamed her own grandfather and misled every purchaser of the book.

The author calls her grandfather a war criminal. By contrast, many Lithuanians consider the grandfather, Jonas Noreika, a war hero who fought to protect his country’s freedom.

Some of the news media have cited this book as support for the proposition that Lithuanians have not owned up to Lithuania’s role in the Holocaust. The media commentators, however, instead of critically examining the book’s contents, mostly appear to be distracted by the fact that it is a granddaughter accusing her own grandfather and don’t get far beyond that.

This is an unusual book on which to rely for facts about disputed historical events which occurred 80 years ago during the worst upheavals of World War II. This book, by the author’s own declaration, is not an objective review of historical facts, but is instead a subjective emotional catharsis of the author’s own beliefs and resentments related to her grandfather and to her own upbringing.

Jonas Noreika, also known as “General Storm,” fought as a partisan and otherwise opposed both aggressors and occupiers of Lithuania – the Germans and the Soviets. He was twice imprisoned by the Germans, the second time he spent two years in the Stutthof concentration camp. Only the war’s ending freed him. But he was then again imprisoned, and this time executed, by the Soviet KGB. These facts are not disputed.

During the German occupation, like other locals who were left to handle the day to day administration of the country, Noreika was initially allowed to remain in his post as Chief of the Šiauliai District. His duties required him to accept and transmit – generally „rubber stamp“ – German orders. Among his other tasks, he signed orders to send Jews to ghettos. That is not disputed either.

And that is where the controversy lies – what did Noreika do in his position under the Germans, and why did he do it? Was he a willing accomplice in support of the German policy to eliminate Jews? Or was he, as others, passing on German orders so that he could survive and continue to use his position to help some of the local population.?

To answer those questions is beyond the scope of this review. The purpose of this review is only to examine what the book itself does or does not accomplish.

The author wrote this book to fulfill a promise to her mother made at her mother‘s death bed. Her mother honored and worshiped her father Noreika, and wanted his legacy as a freedom fighter to not be forgotten. She had been collecting materials about his life with the intent to write his biography. But she fell ill and asked her daughter to write that biography. The daughter has instead written a different book.

In preparing to write this book, the author, acknowledging her modest abilities, enrolled in creative writing courses. Even then, she felt she was not capable of producing a coherent book about her grandfather. She ultimately abandoned her plan to produce „an objective biography,“ and instead decided to write a book about her own „emotional journey“ as she grappled with her grandfather‘s history amid her own problems. Efraim Zuroff, who endorses this book and to whom the author gives „special thanks,“ refers to this book simply as „a tale of personal redemption.“

Thus, the book is an autobiographical presentation of the author‘s personal emotions, resentments and beliefs, as she searches for her grandfather‘s life story. As far as grandfather Noreika himself, the book mostly repeats previously published information intertmixed with many of the author‘s own subjective – that‘s her own word – opinions and speculations.

The author was born in 1961, in an area of Chicago known as „Little Lithuania.“ Her mother was the daughter of Jonas Noreika. Both of the author‘s parents were active in Chicago‘s Lithuanian community. She grew up speaking Lithuanian at home, was a member of several Lithuanian groups, attended Lithuanian Saturday school and summer camp. But she did not do that of her own free will. She did it because her parents demanded it – „I agreed to all their demands.“

The author writes that she grew up in an isolated „nationalistic bubble.“ She now refers to Lithuania as „the comatose country.“ She emphasizes that her mother and grandmother both expressed strong disappointment and disapproval when she decided to marry a non-Lithuanian. She does not hide her resentment of her upbringing, of her family and of Lithuania.

She also reveals some family losses which affected her. As she was preparing the book, both her mother and grandmother, to whom she appears to have been close notwithstanding their disapproval of her marriage, died within a few months of each other. In 2015 her daughter died from a heroin overdose at age 21.

But, as she encounters the story of her grandfather‘s life, whom she has never met, she expresses deeper emotions: „my hands trembled,“ „I had the sensation of falling through a trapdoor,“ „My head started throbbing,“ I stumbled out of my office and poured a glass of wine to steady myself,“ I felt a bewildering torrent of emotions,“ „I began to vibrate with anger,“ etc.

Throughout the book are scattered references to everyday events which bring out strong emotional reactions in the author – her despair after a lost ATM card, her lingering pain after a drunken musician‘s insult at her wedding, her disapproval that a former concentration camp inmate calls his captors Germans instead of calling them Nazis, and other such incidents.

The author‘s research seems to mostly consist of reviewing materials that her mother had gathered and discussions in Lithuania with the few who were still alive of her grandfather‘s fellow partisans and relatives. She dismisses some of them, embdraces others, and forms opinions which she expresses in her book. In many cases it is not clear that objective criteria, if any, she uses to accept one interpretation and discard another.

Among her opinions and suppositions – „could have,“ „it certainly seemed,“ „more than likely,“ „almost certainly“ – her accusation against Lithuanian prisoners in the Stutthof concentration camp especially stands out.

During the German occupation, Lithuania refused to form a Lithuanian SS unit and Lithuanians refused to join the German army. In reprisal, the Germans rounded up 46 prominent Lithuanians, Noreika among them, and incarcerated them in the Stutthof concentration camp. This group of Lithuanians were allowed to write letters to their families and to receive packages. Other prisoners were not.

From this the author concludes that her grandfather was a „Nazi collaborator who enjoyed the privileged status in a concentration camp“ and by such privilege he was being „rewarded for killing Jews.“ Without citing any supporting facts, she goes so far as to state that it was the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler himself, who bestowed these privileges on her grandfather.

But all 46 prisoners, not just Noreika, received the same privileges. Thus, if one accepts the author‘s conclusion, then Heinrich Himmler rewarded all 46 „for killing Jews,“ the reward being imprisonment in a concentration camp for two years in which at least 10 of them were killed or died of starvation. There are not facts to support a claim that any of these 46 prisoners were being rewarded for killing Jews, or that Heinrich Himmler was personally involved.

The author also makes other unexpected statements: „The men who shot Jews....were not the only perpetrators with blood on their hands. Even bystanders who did nothing to prevent or to stop the atrocities were complicit in these crimes.“ As if a civilian bystander had any chance of opposing the German killing machine. To interfere meant being killed yourself. The author shows surprising ignorance of the nature of Nazi Germany.

Eventually, her narrative changes from her grandfather and other individuals to „Lithuania‘s role“ and Lithuania‘s „actions during the Holocaust,“ imputing the acts of specific individuals to all of Lithuania, including to all those Lithuanians who, according to the author, simply by being bystanders had „blood on their hands“ and thus were somehow complicit and guilty.

The Israeli historian, Dina Porat, of course, came to a different conclusion which the author ignores. Historian Porat concluded that 99.5% of Lithuania‘s population was innocent of any direct or indirect involvement in the German organized killing of Jews. According to Porat, the number of Lithuanians who participated directly or indirectly in the killing of Jews was at most 15,000 or one-half of one percent – 0.5% - of the population. The number of Lithuanians who, at the risk of their own lives, sheltered and protected Jews from the Germans is of the same general order of magnitude, if not larger.

Foti‘s book is the latest in a list of publications – mostly internet posts and newspaper articles, but some books as well – which assert that Lithuania is somehow more culpable than other countries for the Jews that were killed during the Holocaust. These publications are generally authored or sponsored by the same activists, some of whose names are listed in Foti‘s book with her gratitude for their assistance and support in producing her book.

This book brings to mind Irena Veisaitė, a prominent member of the Lithuanian Jewish community, a Holocaust survivor, scholar and human rights activist, when she said that there are some people “who never want to acknowledge positive changes in the perception of the Holocaust in Lithuania….and keep repeating the same criticism over and over.”

To properly evaluate Jonas Noreika one should reflect on some difficult questions. The railroad worker who kept the trains running, is he guilty because some of the trains were carrying human cargo to Auschwitz? Is a person to be defined solely by a selected event in his life to the exclusion of others?

Disagreements regarding Noreika’s role, and that of other Lithuanians in the Holocaust, have been debated for 30 years or so. For many Lithuanians Noreika will remain a hero who not only fought for his small country’s freedom, but gave his life doing so. For many Jews he will remain a war criminal.

Because Lithuanians and Jews each view the issue from their own separate experiences, these conflicting views may never be reconciled. Perhaps only time can eliminate some the sharp edges from these debates.

Judged as a literary or biographical work, Foti’s book is highly flawed.

From a historical research perspective, the book presents no significant new facts, with the possible exception of perhaps shedding some additional light on whether Noreika could have been present in Plungė when that city’s Jews were rounded up. What facts the author does present are often so intertwined with speculations about Noreika’s life and with narratives of the author’s personal problems and resentments, that it is easier to find those facts in other and more credible sources.

A book about Noreika might have contributed to our knowledge of that terrible and tragic time. This is not such a book. But then, it was never intended to be. The author has instead written a personal chronicle of her own “emotional journey.”

Meine Rezension: https://alles-ueber-litauen.de/litauen-buecher/silvia-foti-noreika

Rezension der Rezension ;-)

Die Buchrezension von Donatas Januta aus der amerikanischen Publikation von LITUANUS.org möchte ich gerne vorstellen, weil sie meiner eigenen Rezension diametral widerspricht. Natürlich hat Januta in manchen Dingen Recht. Der Titel des Buches (The Nazi’s Granddaughter) ist ziemlich martialisch, er vermutet um Aufmerksamkeit zu gewinnen, die Fakten waren größtenteils schon durch Evaldas Balciunas bekannt. Und angeblich gab Silvia Foti zu, dass auch sie nicht glaube, dass ihr Großvater ein Nazi gewesen sei. Auch der Aufenthalt im KZ Stutthof zeugt von einem Konflikt mit den deutschen Besatzern.

Trotzdem führt die Rezension von Januta auf die falsche Fährte. Erstmal hat Jonas Noreika eine Vorgeschichte. Er hat das Heftchen "Pakelk galvą, Lietuvi!!!" verfasst, offen antisemitisch, nationalistisch, passend zu bestimmten Kreisen, nicht nur in Litauen zu dieser Zeit. Dann war er Chef der LAF (eine Antisemitische Terrororganisation die mit den deutschen Nazis den Überfall auf die Sowjetunion (oder Litauen) plante. Noreika war dafür im Memelland und dadurch den Deutschen bekannt. Er bekam den Posten als Chef des Verwaltungsbezirks Siauliai am 3. August und löste den weniger radikalen Ignas Urbaitis ab. Sofort wurden die Gesetze zur Abgabe von jüdischen Vermögen verschärft.

Januta argumentiert, Noreika hätte „nur“ die Befehle von Gebietskommissar weitergegeben (weitergeben müssen) und was wäre ihm anderes übriggeblieben? Er wollte doch seinen Landsleuten helfen. Das konnten die litauischen Patrioten nur in diesen hohen Positionen.

Wollen wir wirklich die Arbeit der litauischen Verwaltung damit legitimieren, dass sie ihren Landsleuten helfen wollten? Machen wir uns nichts vor. Die Litauer wie Noreika halfen den Deutschen so lange, wie sie ein gemeinsames Ziel sahen. Ohne litauische Hilfe hätten die Deutschen mit ihren wenigen Mitarbeitern gar nicht ihre Arbeit machen können.

Widerstand von konservativen Litauern (also Leuten wie Noreika, die mit den Deutschen zusammenarbeiteten) kam erst bei der Bildung von SS-Legionen. Das war Anfang 1943, in einer Zeit also, als die meisten litauischen Juden schon tot waren. Bis dahin haben die Litauer problemlos mitgemacht. Nun brauchten die Deutschen aber Soldaten. Internationale Gesetze verbieten aber die Aushebung von lokaler Bevölkerung in die eigene Armee (verwunderlich, dass sich so ein Schurkenstaat wie Hitlers Deutschland sich an solche Gesetze hielt), weshalb es zu SS-Verbänden kam.

Warum der Protest so spät spürbar wurde, hat damit zu tun, dass die ethnischen Litauer nun langsam merkten, dass nach den Juden nun sie selbst auf dem nächsten Treppchen der Rassenleiter standen (frei nach Raul Hilberg).

Balys Sruoga beschreibt den Alltag im Konzentrationslager Stutthof sehr eindrucksvoll. Es gib eine gute Übersetzung von Markus Roduner. Es kamen wirklich 10 der 46 inhaftierten Litauer um und die Haftbedingungen müssen besonders am Anfang grauenhaft gewesen sein. Irgendjemand auf deutscher Seite gewährte den Litauern aber plötzlich den Status "Ehrenhäftlinge" und danach hatten die Litauer, zumindest schreibt es Balys so, ein einigermaßen auskömmliches Leben. Wenn man das über Stutthof sagen kann.

Donatas Januta schreibt, dass die Unbeteiligten nichts an den Judenmorden ändern konnten, sie waren machtlos den Nazis gegenüber. Leider schreibt er nichts über die Bereitschaft dieser "Unbeteiligten" sich am konfiszierten Gut der Juden zu bereichern, auch als diese noch nicht tot waren. Eine Anmerkung zur litauischen Kooperation bei den Massenmorden wäre hilfreich gewesen. Denn die Deutschen konnten aufgrund von Personalengpässen ohne die Litauer nichts machen.

Januta verwehrt sich auch gegen die Behauptung, in Litauen wäre der Verfolgungsdruck noch größer gewesen als in anderen Ländern. Zugegeben, ich kenne die Situation in anderen Ländern nicht (auch wenn die Prozentzahl der getöteten Juden in Litauen wohl die höchste ist). Allerdings schreiben jüdische Autoren über die feindliche Haltung vieler Litauer, so dass sie tatsächlich das "schützende Ghetto" der vermeintlichen Freiheit vorzogen.

Interessant ist Donatas Januta Schlussfolgerung. Er fragt, ist ein Bahnmitarbeiter schuldig, wenn "seine" Züge nach Auschwitz fahren (der Vater von Ex-Präsident Adamkus war höherer Bahnmanager in Litauen)?

Ist eine Sekretärin im KZ Stutthof schuldig (in Deutschland ist 2022 eine betagte Dame angeklagt in eben dieser Sache)?

Ist denn überhaupt jemand schuldig?

Und wenn man meint, irgendjemand muss ja die Verantwortung an den Verbrechen der Jahre 1941 bis 45 tragen, kann man Leute in so hohen Verwaltungspositionen wie Jonas Noreika nicht aussparen. Warum will man ihn dann ehren?